PART ONE

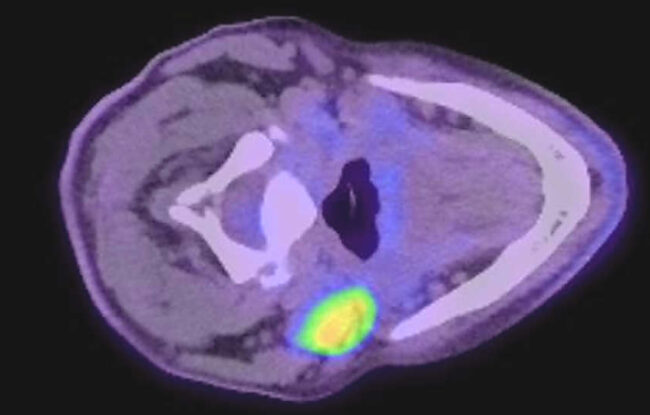

The term oropharyngeal cancer applies to any cancer that arises from the area at the back of the mouth which forms the top part of the throat which includes the soft palate, palatine tonsils, lingual tonsils and tongue base. The most common cancer is a squamous cell carcinoma. Other cancers such as adenoid cystic carcinoma or mucoepidermoid carcinoma arise from minor salivary glands. Lymphoma can also occur, arising from the tonsil tissue of the oropharynx.

There were 3 distinct periods of management:

1. 1992-2000; the primary treatment for oropharyngeal cancer was surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy.

2. 2000-2010; there was a swing away from surgery to primary treatment with chemoradiotherapy. It was during this period when it was recognised that the major cause of oropharyngeal SCC was due to the human papilloma virus (HPV).

3. 2010-2025; the application of the da Vinci surgical robot in the treatment of HPV associated oropharyngeal SCC. Providing a less invasive and precise surgical approach which has revolutionised the management of oropharyngeal cancer. Enabling a significant number of patients to avoid radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The traditional approach to the oropharynx

One of the most common ENT operations is tonsillectomy performed using a headlight with no magnification. In cancer management the problem with this approach was that the tumour was never completely removed.

Open approaches to the oropharynx are complex. In nearly all cases, replacement of the excised tissue was required using vascularised tissue, in the form of a rotation flap or free flap. This was necessary to prevent saliva leaking out of the throat and into the neck. Patients were in hospital for approximately 2 weeks, requiring a temporary tracheostomy and nasogastric tube feeding until the wounds were healed. The procedures were associated with a significant number of complications.

The open approaches can be classified as:

1. Mandibulotomy and mandibular swing; incisions in the neck and through the lower lip to expose the mandible, which was then cut with a saw, then incisions along the floor of the mouth to allow the mandible to be swung outwards and enabling access to the oropharynx.

2. Lingual release/tongue dropout; this approach avoided cutting the mandible, incisions were made on the jawbone and in the neck and then connected, allowing the floor of mouth and the tongue to be pulled through into the neck and allowing access to the oropharynx.

3. Lateral pharyngotomy; in this operation an incision was made in the neck followed by an incision in the side wall of the pharynx.

Conclusion

The management of oropharyngeal cancer has undergone a huge change over my career. Minimally invasive surgical approaches pioneered using the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser provided the confidence to explore other evolving technologies. The result was the development of Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS) using the da Vinci robotic platform.

Since 2011 I have performed most oropharyngeal cancer surgeries using the robot. The skills to perform open procedures are important and I am pleased to have mentored many younger surgeons in these techniques. Yet when I recall lengthy and complex operations with difficult recuperations it is very clear to me that the decision to adopt new technologies early on was the right one.

Part II of this blog will explore TORS and the ongoing evolution of robotic surgery.